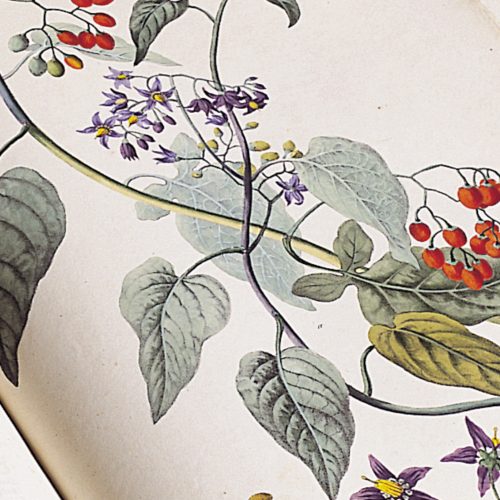

The Bibliotheca Antiqua of Aboca Museum is an important collection of ancient books related to the specific theme of medicinal plants.

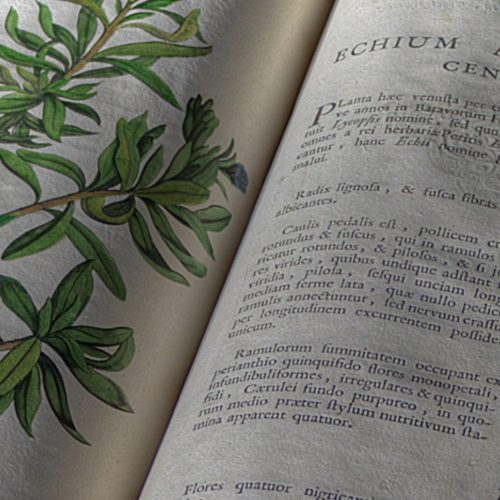

The collection of 3000 books, published from the earliest days of printing until the first decades of the 20th century, documents the development of human knowledge on the curative use of plants. The most important type is represented by herbaria, indispensable for the identification of plant species and for the description of their virtues.

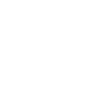

Over the centuries they have become works of art thanks to fine illustrations that testify the evolution of printing techniques with the magnificence of colors, phytographic precision and the evidence of scientific details.

The images contained in them show how the osmosis between the work of the artist and the scientist makes concrete the idea of the beautiful, the extraordinary and the accomplished, typical of a work of art within an instrument whose purposes remained purely medical: Art at the service of health.

The Bibliotheca also contains several volumes on pharmacology, chemistry, medicine and the little “books of secrets”, custodians of popular knowledge; a section is dedicated to precious prints, a valuable source of images for the Museum’s publications, another one to the handwritten prescriptions of doctors and apothecaries.

The last ambitious project is to collect herbs and flowers that describe medicinal plants of all continents, in order to have a rich documentation, useful for a botanical, historical and scientific comparison.

The Bibliotheca Antiqua, located on the third floor of Bourbon del Monte Palace, can be consulted for studies or researches, upon reservation only.